A national willingness to forget that obligation because we somehow perceive these children as not being one of us is an attitude that we cannot afford. It is a statement of, “We care for children, unless…”

“Othering”. Simply put, it is the mental commitment to the idea that someone does not belong. It creates a mutually exclusive pair of categories – one of us, and not one of us. And it is the very act, I fear, that allows many among us to feel nothing in the face of the conditions in which thousands of unaccompanied minors are being detained.

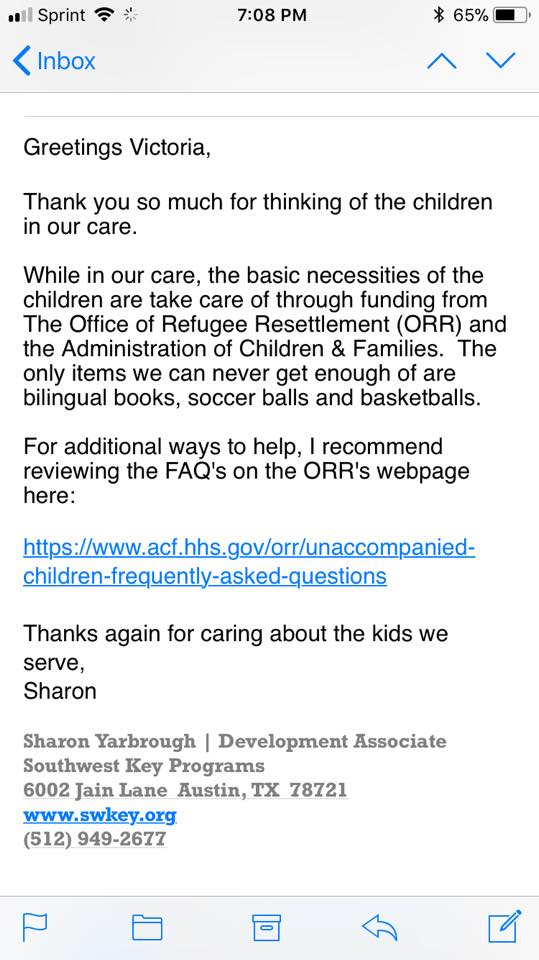

Over the weekend, I sent an email to Southwest Key – an organization that runs 26 facilities for “unaccompanied minors”, asking if there was a process for donating food and clothing, as well as whether there was a possibility for American families to foster any of these unaccompanied minors. I had hoped that, upon receiving a response, I might be able to write a very different kind of blog post.

I had hoped to be able to talk to you today about steps by which one might provide a safer, more home-like environment for children who, regardless of whether or not you agree with the actions of their parents or the circumstances of their arrival, have undergone the trauma of family separation and require not only a roof over their heads and food in their bellies, but also stability and nurturing in order to mitigate the long-term impact of that trauma on their lives.

Unfortunately, that is not the blog post I am able to write.

Less than two days after sending out a general email, I received the following response:

While I want very much to rest easily and believe that I no longer need to be concerned about the thousands of children living in settlements run by Southwest Key and many other organizations, when I take this response and weigh it against reports of violations in these shelters like failing to have minors treated for STI’s that could impact their long term fertility and health, and administering foods and medicines to which children have documented allergies, I hesitate.

Southwest Key receives hundreds of millions of dollars in government money to operate these settlements for unaccompanied minors – it received over 100 million dollars in May 2018 alone. Even if you believe that these children should not have been brought here, even if you disagree fundamentally how they arrived and want to feel nothing towards them, you must realize that government dollars – your tax dollars – are going towards these shelters, and you should have an interest in how they are run. This is not politics. It does not matter whose policy it is. It does not matter whose fault it is. It matters who is going to step up and take steps towards fixing it. Despite the widespread publicizing that an executive order represents something actually being done, no one has truly taken those steps.

The government estimates that it costs anywhere from about 170 to 300 dollars to provide food for one child one month. Last fiscal year, Southwest Key served about 11,000 children – the cost of food alone for the average length of stay of 56 days in and of itself represents a multi-million dollar cost. Apart from this, the salaries of the top 3 executives of this organization approximately tripled between 2012 and 2015, totaling about 1.6 million dollars.

There is then the matter of staff. Among others, Southwest Key employs case managers whose duties include the following:

- Conduct initial intake interviews of youth to include gathering familial, possible sponsorship information and to establish age of the youth.

- Conduct interviews of family members, friends of family and/or sponsors to determine the integrity of the relationship and verify information received from minor within 24-48 hours upon admission to the shelter.

- Determine options available for youth within 48-72 hours and proceed with the required documentation to reunify youth with family in home country or in the United States as deemed applicable.

- Coordinate with local pro bono attorneys for the timely provision of “Know Your Rights” presentations to youth and ensure youth signs the acknowledgment and receives a copy of the Legal Service Provider list and Notice to Juvenile Aliens in Federal Facilities Funded by DHS or HHS.

- Ensure the timely completion of (assessments) Initial Intake, Emergency Placement, and Preliminary Service Plans in accordance with SWK, State, and Federal requirements. Additional assessments may be required depending on the location of the program and state licensing requirements. Forms are subject to change at any time.

- Ensure the timely submission of the initial Individual Service Plan due within 21 days of the youth’s arrival to the shelter and 30 day updates thereafter in accordance with SWK, State and Federal requirements.

- Document all actions taken and contacts with youth, sponsor, and stakeholders in the form of progress notes (efforts) as required by SWK, State and Federal contracts.

- Complete and submit reunification packets for initial review to Lead Case Manager or Designee. (if applicable)

- Submit completed reunification packet with appropriate referral made by Case Manager for the timely release of youth to designated ORR representative.

- Provide weekly face to face updates to youth and telephonic updates to family members/sponsor with documentation found in ETO.

- Ensure the provision of two weekly telephonic contacts with family of origin, primary caregiver and/or sponsor.

- Facilitate incoming calls to minors with the appropriate family members and other approved caregivers.

- Facilitate attorney to client contact as requested by youth.

Recurring themes in Glassdoor reviews from employees include a lack of behavioral health expertise or valuing of staff from leadership, as well as limited staff development opportunities and less than competitive pay. Most former and current employee reviewers stated that the highlight of working for the organization was the ability to work with and make a difference for the children.

It truly, genuinely seems like the staff at Southwest Key is at least significantly comprised of well-meaning social services professionals and clinicians working for a non-profit, wanting to do what they can with limited time and resources, burning out and suffering from poor work-life balance in the effort to do something for these kids who risk being lost in the system. This is a plight that is all too similar to that of our own child welfare personnel within the United States.

Having worked alongside child welfare staff for three years of my nursing career, I can say with the utmost confidence that the efforts they put into doing something for children thrust into a system against their own choosing is astonishing – while the external perception of the child welfare system is not always a positive one, you truly cannot see the painstaking efforts to help that occur unless you have been on the inside.

It’s this view from the inside that I was privileged enough to have that leads me to fear the implications for all of us if we allow this “othering” of children to continue. It already happens every day to the children within our existing, domestic systems. They are traumatized prior to their involvement in the system. They are further traumatized by the process through which they enter the system. They are stigmatized and identified by many based on what others perceive the crimes of their parents to be.

The scrutiny, criticism, and skepticism that is so frequently leveled against our own child welfare service agencies shows that we know – we need to heal these kids from past and present wounds, physically and mentally. We need to do better by them. It does not matter what their parents did or did not do. It does not matter what nation they are citizens of. They are children and we are obligated to do better by them.

A national willingness to forget that obligation because we somehow perceive these children as not being one of us is an attitude that we cannot afford. It is a statement of, “We care for children, unless…”

…unless they have arrived undocumented.

…unless their parents have committed an illegal act.

…unless we view them and their parents as different or dangerous.

We cannot place prerequisites on our willingness to care, or to do better, or to be better. We are obligated to be better. We are obligated to change how we think. We are obligated to open our minds and hearts to those we see as others, because only then can we actually embrace and heal children – our children, citizens, non-citizens, and asylum-seekers alike.